first here and then far, Harbour Publishing 2024

Japanese Mallow

When the inevitability of my mortality

overwhelms me momentarily, I . . .

touch these repeating pink blossoms

their delicacy softens self-sorrow

makes dying a mere event among lives

continuing to thrive: those bolstering me

(not by bluster) by showing how, exemplars

of one-who-calms-down, fathers who help

finish homework, moms with nightly rhymes

also you I’ve never met, who know me

as sentences, not an entirely true reproduction

but close, the way wind grasps petals it takes

to drop first here and then far

from the tilting, un-mournful mother plant

the trick of staying and leaving Harbour Publishing 2023

From the trick of staying and leaving

‘funny’

Miro points to a row of second-floor windows

(on some ulica/street whose name escapes)

each ornate in history’s way, and tells me

he spent years in those bright rooms

singing in a choir, ‘a funny time,’ he says

and several steps later as we cross

tram tracks, I ask, ‘funny how?’

in Canada we might mean

those days were somehow oddly off

but he explains, ‘a time without problems’

and I understand, ‘a time of fun’

even small differences continue to surprise

and reveal who each of us is, what

our cultures and languages have made

like his number 1 with its slight

tilt with an added angle at the top

that risks becoming a seven, as if

haunted by a touch of the Cyrillic

and he has little use for ‘I’ because

when admiring a house, for example

his grammar leads him to say ‘it likes me’

and so his world is animated, filled

with metaphor cheerfully directing

its attention onto him, greeting him daily

while his Canuck friend must search

in himself, object after object singled out

to find what is enlivened out there

and so misses the rush of feeling from the world

continuously coming to embrace him

watching for life

the Crow lands, infused with purpose

to explore a bag, perchance to find

the model morsel, the French fry

discarded or perhaps a crumb

of dignity in the doughnut not yet

mouldering, he steps close, closer

pecks and – behold! – is rewarded

his sunlit beak spies and digs and rips

he thinks neither ahead nor behind

tipping back to swallow the tidbit

I think of his feathers, black black, how

they absorb light, the dark hole

he brings wherever he lands on earth

always a purity of disappearance

his piece of night that darkens day

the underside of a shoe that waits

at the back of the closet whose doors

are locked, the key a child dropped

in the forest, moss swallowing it

and now Crow turns and the sun

flashes in his wings, a spark

and again the flash comes, lightning –

a sudden storming – to show me

that where black is, white will also be

if only briefly, yet briefly

suffices to make me look again

where I might have missed this

balance, his way of making light

watching for life McGill-Queen’s 2022

the bridge from day to night Harbour Publishing 2018

the bridge from day to night

driving back on the Second Narrows

I see the mountains of North Van

rise higher than I imagine

they can, they keep going

up and up, and from the apex

of the bridge with traffic flying

I look directly into

their deepest clefts:

a bear drifts on the trail

sand a hiker half falls down

the slope, one arm out

for a sapling to swing around

it’s home (box in a box)

that will save me (if not him)

yet I sometimes can’t decide

should I go up the Cut

or turn on Main, the only options

I see right now, though late at night

when I give up the day

I dream the bear comes calling

Zoo and Crowbar Guernica Editions 2015

Zoo and Crowbar

Zoo and Crowbar, a novella, which early readers have described as a fable about one person’s experience of the end of our world; a hypnotic, disconcerting human dream that knows infinitely more than the dreamer and is still the dreamer; a retelling of The Pilgrim’s Progress from This World to That Which Is to Come.

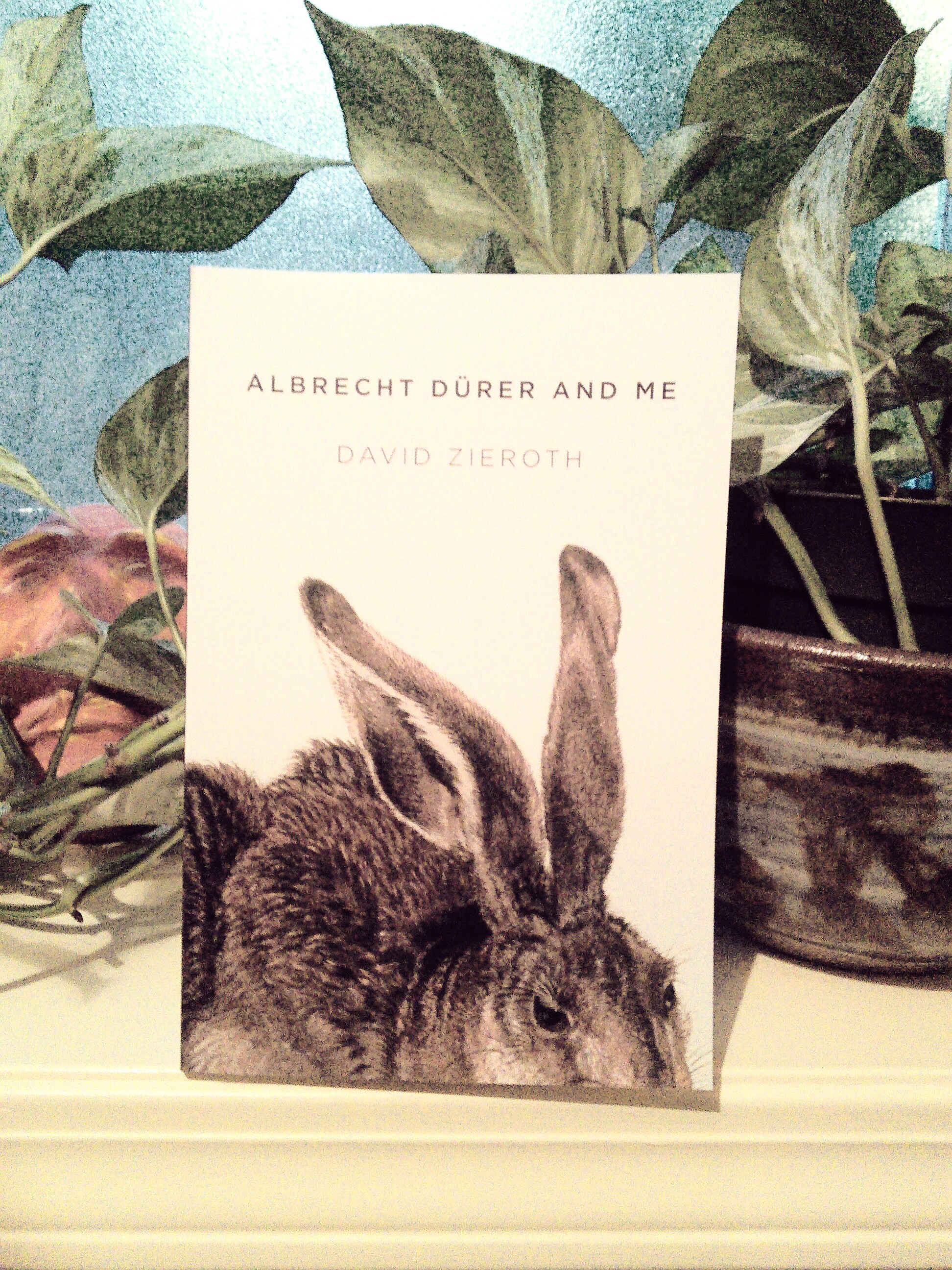

Albrecht Dürer and me Harbour Publishing 2014

Hay Day Canticle Leaf Press 2013

Crows do not have Retirement Harbour Publishing 2011

The November Optimist Gaspereau Press 2013

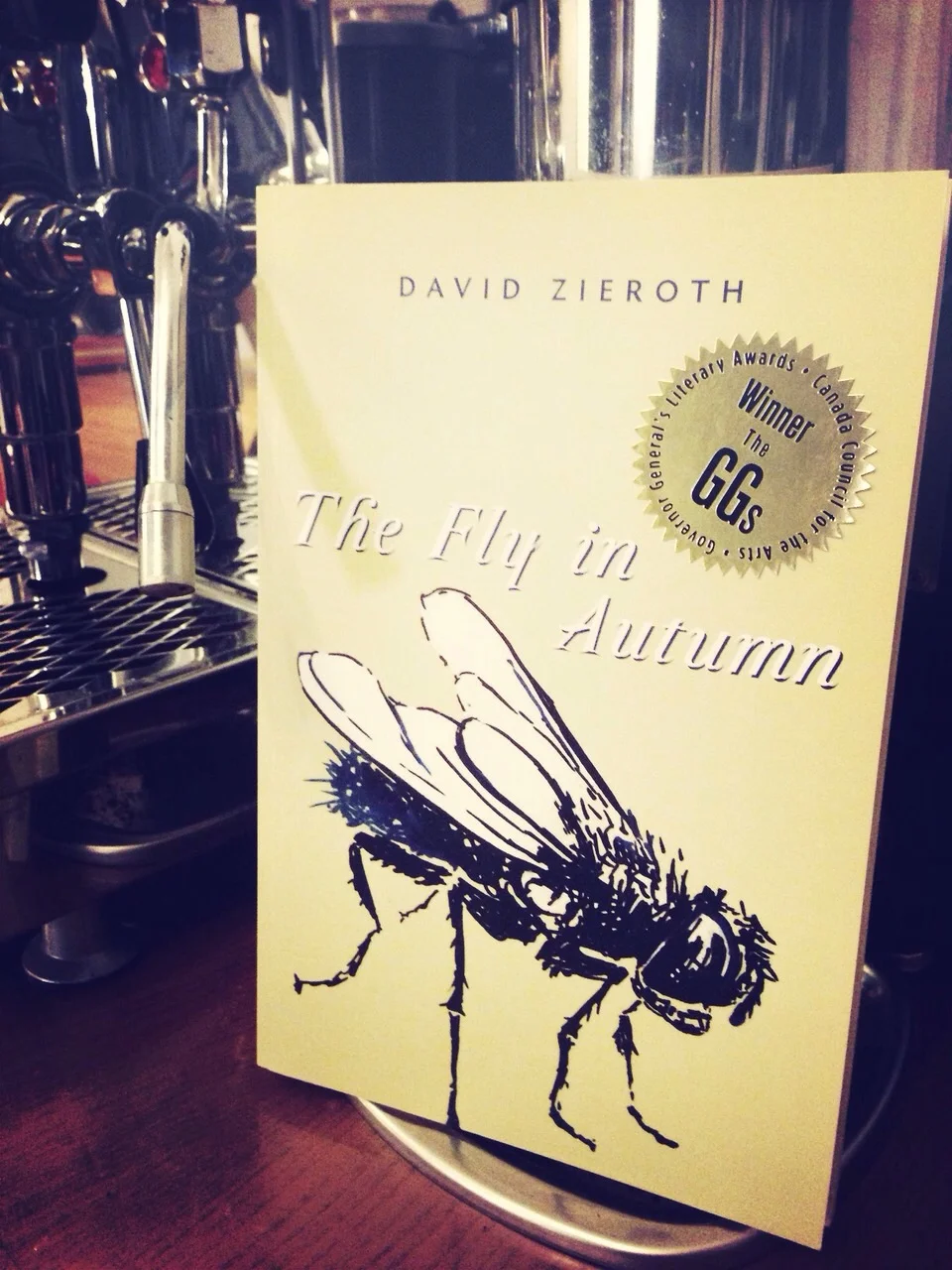

The Fly in Autumn

Winner of the Governor General’s Literary Award for Poetry 2009

The Fly in Autumn Harbour Publishing 2009

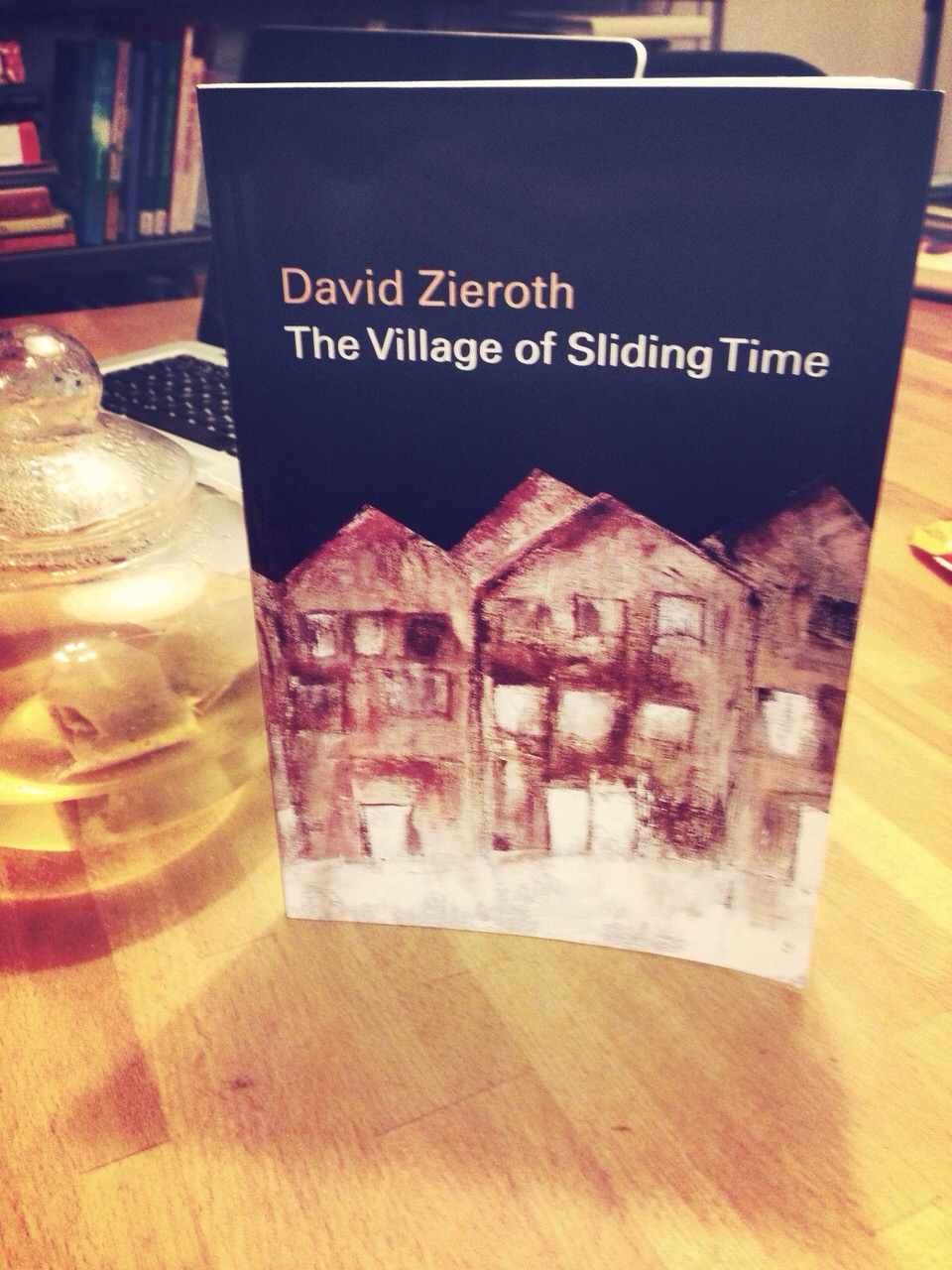

The Village of sliding Time Harbour Publishing 2006

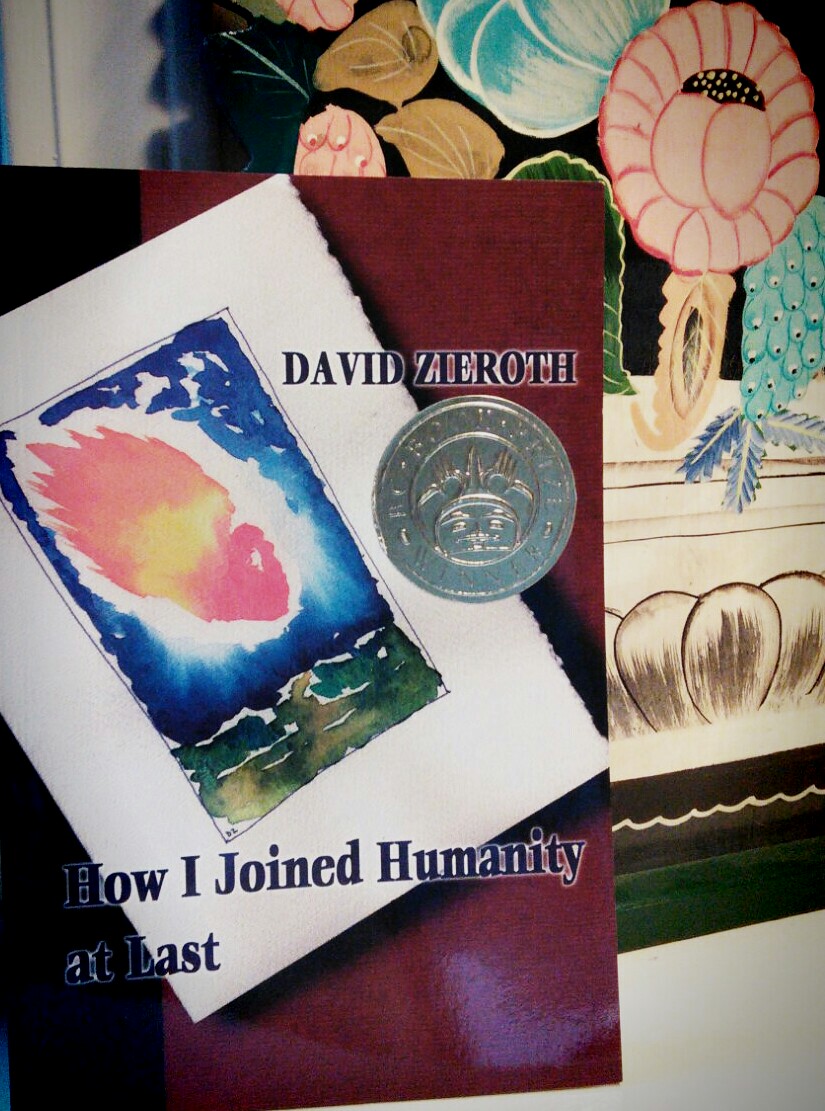

How i Joined Humanity at Last Harbour Publishing 1998