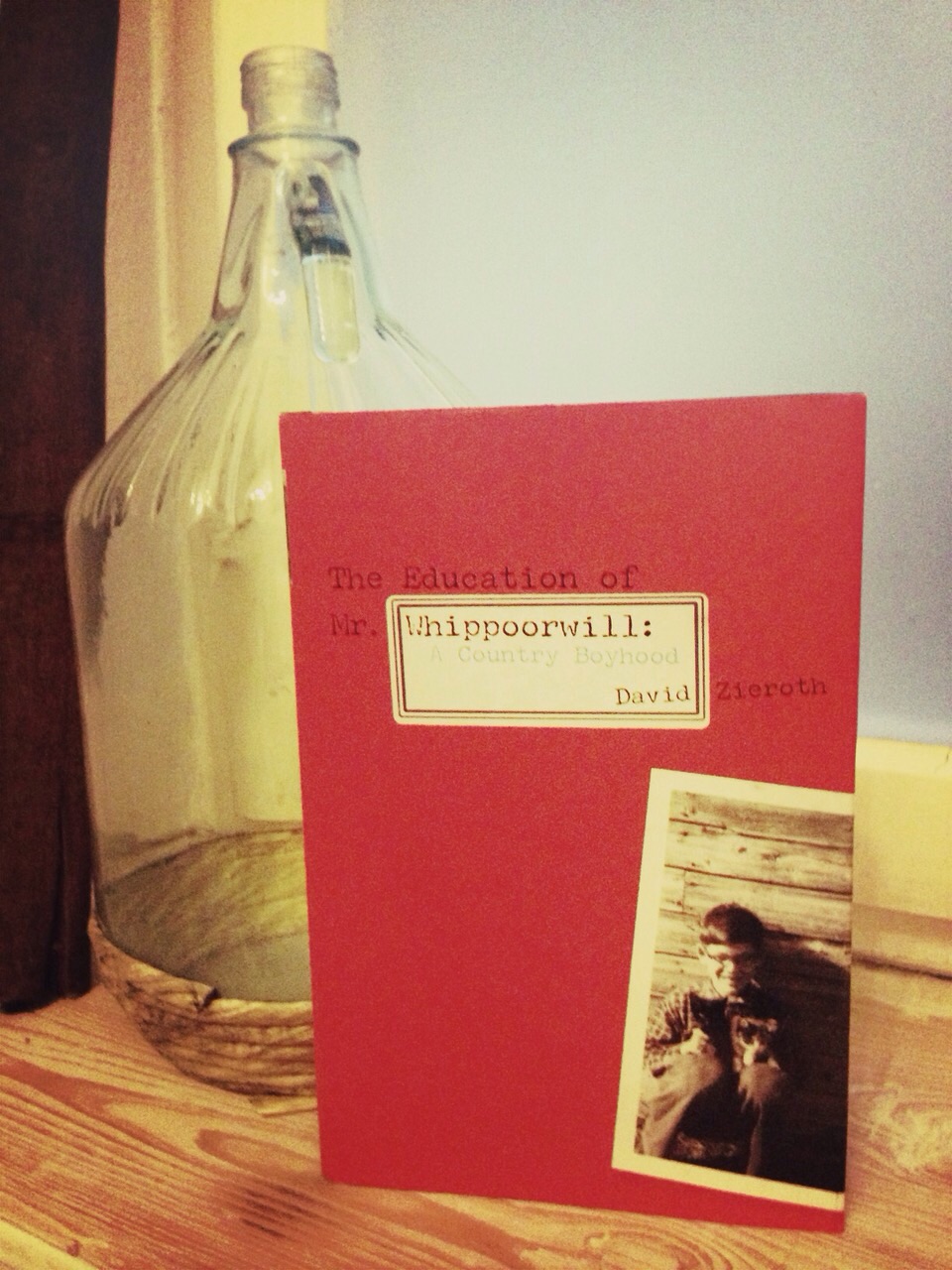

The Education of Mr. Whippoorwill Macfarlane Walter & Ross 2002

How my dad selects which pig to kill I don’t know. They’ve all been fed the same mixture of chopped oats and water, along with slop from the house—potato peels, corn cobs, carrot tops, wash water—and they all complain so noisily at the trough you would think we hadn’t just fed them that morning. They all look the same to me, not like the cows with their differences of brown and white and personality. One pig might be a little bigger than another, but they all have that same rounded back, those floppy ears we have to check for sunburn, that wrinkled snout that’s capable of eating almost anything. I know, because once I saw them corner an old hen.

One day Fritz comes with his big truck. He’s a gentle man with thick white hair and a calmness that must come from hauling so many animals to the meat packers: calves, cows, steers, an occasional horse, now pigs. I’ve seen him pushing a calf, twisting its tail until its eyes bulge and it shits wildly, its hooves slipping on the slimy truck deck. Pigs are easier to move, more likely to run up the ramp together. As the circle of men in the pen grows tighter and the pigs’ squeals louder, one pig makes a dash up the ramp. Soon the others follow, the gate in the back of the truck is dropped, and they’re on their way.

Each pig gets a whack from Fritz’s hammer, a stamp that tells him which farmer this pig belongs to when he pulls into the auction. Dad’s sure he’s only raising A-grade pigs, and when he finds out later that one of them was sold as B-grade, he gets mad, saying something to himself I can’t make out. But it’s too late, the pigs are gone.

Except for the one he’s chosen for us.

This compelling memoir, like the Manitoba landscape of David Zieroth's childhood, is elegant and spare. With a beautiful clarity he brings to light the everyday events—sometimes lovely, sometimes banal, sometimes cruel—that shape a life. The Education of Mr. Whippoorwill is the poignant story of a boy's search for the man within himself. It is also a history of how rural dwellers come to know, and to learn from, the land, their families, and their communities—a way of learning that, unfortunately, is vanishing.

Sandra Birdsell, from the book jacket

Reviews

As a young man at the end of the book, weeks after his father has died, Zieroth says, “I become, suddenly, vividly, mindful of my father’s traits in me, perhaps the very ones he received from his father.”

The lovely symmetry of these observations—the looking ahead as a boy, the looking back as a man—is only one of many delights in The Education of Mr. Whippoorwill, a touching, humorous, crisply written book that stands out from the welter of flabby, overwritten tomes crowding the bookstores these days.

Dave Williamson, The Globe & Mail

There is a sweetness that runs through this book. It’s not saccharine, but rather the sweetness of freshly mown grass. It is the delicious taste of discovery, of learning how to be “somebody else,” of learning about sex, of being grown up.

Perhaps even more than a book about his own life, The Education of Mr. Whippoorwill is a kind of paean to Zieroth’s father, a statement of the powerful, respectful love he always held for him.

And there is yet another thing about this quietly told book: It is an exploration of what it means to be moving on, to find and define oneself. There is that sense of ambivalence we have all felt, which Zieroth, describing himself at university, expresses so correctly: “I worry that I might change and that I might not.”

Heidi Greco, The Vancouver Sun